"Her bejeweled hands lay sprawling in her amber satin lap. Her tags and ear-rings twinkled, and her big eyes rolled about. She was doing nothing with perfect contentment, and thinking herself charming. Anything so becoming as the satin the sisters had never seen." (Chapter 21)

George himself refuses to marry her because of her dark skin and it is from him that we learn of Miss Swartz Jewish lineage:

"Her father was a German Jew—a slave-owner they say—connected with the Cannibal Islands in some way or other. He died last year, and Miss Pinkerton has finished her education. She can play two pieces on the piano; she knows three songs; she can write when Mrs. Haggistoun is by to spell for her; and Jane and Maria already have got to love her as a sister." (Chapter 20)

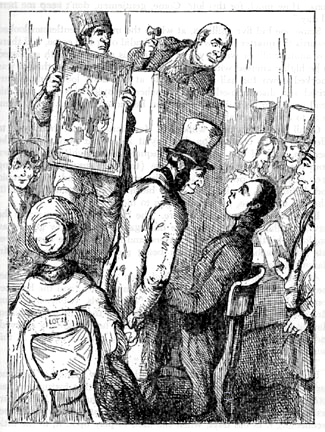

Other Jews appear in the novel when Becky and Rawdon Crawley attend an auction at the home of the bankrupt Sedleys. Becky comments to her husband,

"Look at them with their hooked beaks," Becky said, getting into the buggy, her picture under her arm, in great glee. "They're like vultures after a battle."

The derogatory comment was accompanied by the illustration above.

Thackeray himself was not anti-Semitic, though he had negative encounters with Jewish financiers in the 1830s. However, in his portrayal of Miss Swartz, he gives her no depth of character, though she has much affection for Amelia. She has basically no skills and the only reason George's sisters like her is her wealth. His description of those at the auction as vultures, unclean birds, is ironic when one considers who makes the comparison.

Sources

Israel at Vanity Fair: Jews and Judaism in the Writings of W.M. Thackeray by S.S. Prawer

Rhoda Swartz in Vanity Fair: A Doll without Admirers by C.J. Hegler