The final chapters of Part 3 reveals Aglaia's desire to marry Myshkin and the latter's willingness to consent. At the beginning of Part 4, Ganya is informed by his sister Adelaida of the engagement, and, surprisingly, does not appear to be perturbed by the revelation. Though in love with Aglaia himself, Ganya resignedly accepts the ensuing marriage as a done deal. Instead, he is more worried about his father being found out a thief.

Ganya is a man of "violent and envious cravings," desperately desiring "to prove to himself that he [is] a man of great independence." He has given up his job as secretary to General Epanchin and has no idea what to do now, though he feels he will have success of some significance. Myshkin identified him in Part 1 as one who strongly desires to be original. Marrying Natasya was one attempt at originality, having no love for her and only desiring the monetary gains to be enjoyed by the match. The lack of originality causes 'the continual mortification of his vanity" to be even greater.

Why is Aglaia not interested in Ganya? One only need to remember her recitation of "The Poor Knight" to know what attracts her to Myshkin. Myshkin grasped an ideal and believed in it, despite what others said. There is no ideal in mind for Ganya. As a matter of fact, one is not sure what he really stands for. The arranged marriage with Natasya shows he is corruptible. There is no innocent quality about him like there is about Myshkin.

A blog detailing particularly novels, but also poems, plays, and social essays from the Victorian era, though strict adherence to the period of Queen Victoria's reign (1837-1901) may not be observed. Blog will also feature some American, French, and Russian works of the period.

Wednesday, March 31, 2010

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Holbein's Christ

Ippolit continues his explanation by describing his encounter with Rogozhin. The two only recently met, and, despite Ippolit's declaring how different they are, one similarity they share is their aversion to Myshkin. Though Ippolit chooses not to disclose the details of their conversation, one figures Myshkin must be an explored topic.

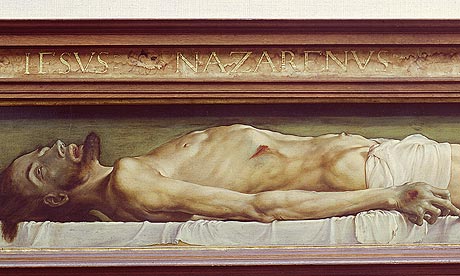

Ippolit accompanies Rogozhin to his home and comments that it is "like a graveyard." Not only does this description correspond with Myshkin's description but it contrasts directly with Ippolit's earlier pursuit of life. Now he is making acquaintence with a potential murderer who obviously does not value life. While at Rogozhin's home, Ippolit also notices the Holbein painting and is captivated by it. He notes how other artists have painted Christ in the beauty of his sacrifice but Holbein's work has "no trace of beauty." Instead, there is agony in every detail, having the "look of suffering in the face." Ippolit does not understand how nature, which he calls "a merciless, dumb beast," could be so cruel to a perfect being. Christ is depicted devoid of divinity, not appearing as the Son of God but as an individual recently beaten to death.

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Life Among the Trees

Ippolit shows up at Myshkin's villa and delivers his "Essential Explanation," his final thoughts before he dies. He begins by explaining his reason for coming to Pavlovsk. At first he was content to lay in his bed in St. Petersberg and die alone, having no desire to experience life any longer. His only view of the outside world was Meyer's brick wall outside his window. Nevertheless, he was invited to Pavlovsk by Myshkin, not to die but to live. This statement changed his entire perspective, so that he went Pavlovsk to see people and the trees, leaving behind Meyer's wall.

Ippolit shows up at Myshkin's villa and delivers his "Essential Explanation," his final thoughts before he dies. He begins by explaining his reason for coming to Pavlovsk. At first he was content to lay in his bed in St. Petersberg and die alone, having no desire to experience life any longer. His only view of the outside world was Meyer's brick wall outside his window. Nevertheless, he was invited to Pavlovsk by Myshkin, not to die but to live. This statement changed his entire perspective, so that he went Pavlovsk to see people and the trees, leaving behind Meyer's wall.Ippolit became attracted to living things, instead of the inanimate wall. He began talking to his best friend Kolya about other people's lives. He became greatly interested in how people used the life they were given. He states, "I clutched at life, I wanted to live." He tried to grasp how people could be unhappy while they still had life. He describes Surikov, a widowed man that lives in poverty whose baby daughter froze to death. Even in his unfortunate condition, Surikov still has life: "If he's alive he has everything in his power. Whose fault is it if he doesn't understand that?" Ippolit is almost envious of his condition because he still has the ability live.

The above painting is Landscape with a Goatherd and Goats (1636-7) by Claude Lorrain.

Thursday, March 18, 2010

A Sacrifice

Part III remains in Pavlovsk and begins with the suggestion that Aglaia has begun to develop feelings for Myshkin, feelings which likely started during her recitation of The Poor Knight. Though Madame Epanchin seems to be the only one to recognize her daughter's change in heart, circumstances later reveal that Aglaia had refused an offer from Radomsky a month earlier and has been in communication with Natasya, who reappears in this section. Natasya wants Myshkin to marry Aglaia and refuses to marry Rogozhin until their marriage.

Though Myshkin states he has no feelings for Aglaia, Natasya is convinced that the two must marry, though she herself loves Myshkin. Suddenly, Myshkin and Natasya have reversed roles from earlier in the novel: whereas Myshkin had been willing to sacrifice himself to loving Natasya, now Natasya is willing to make sacrifices. Her sacrifice is twofold: she is sacrificing her love for Myshkin by giving him to another that won't "ruin" him; also by promising to marry Rogozhin, she is giving herself to a man she believes will kill her. Nevertheless, she places Myshkin's well-being above her own.

Though Myshkin states he has no feelings for Aglaia, Natasya is convinced that the two must marry, though she herself loves Myshkin. Suddenly, Myshkin and Natasya have reversed roles from earlier in the novel: whereas Myshkin had been willing to sacrifice himself to loving Natasya, now Natasya is willing to make sacrifices. Her sacrifice is twofold: she is sacrificing her love for Myshkin by giving him to another that won't "ruin" him; also by promising to marry Rogozhin, she is giving herself to a man she believes will kill her. Nevertheless, she places Myshkin's well-being above her own.

Monday, March 15, 2010

Ippolit

Towards the end of Part II, Dostoevsky gives the reader a clearer portrait of Ippolit, who had been introduced momentarily earlier in the novel. He is the best friend of Kolya and the 17 year old son of Gen. Ivolgin's mistress.

He had an intelligent face, though it was usually irritated and fretful in expression. His skeleton-like figure, his ghastly complexion, the brightness of his eyes, and the red spots of colour on his cheeks, betrayed the victim of consumption to the most casual glance. He coughed persistently, and panted for breath; it looked as though he had but a few weeks more to live.

He appears in Part II with the band of accusers of Myshkin who seek to extort money from the prince. Though he apparently is unaware of the plot, he tries to help make the case that the prince should surrender his inheritance. When Ganya reveals the truth, Ippolit accepts it, though he is offended that Myshkin will still attempt to offer some money to his accusers.

Kolya describes him as clever but a "slave to his opinions." An atheist, Ippolit describes nature as ironical and accuses Christ of being leader of a genocidal movement:

"Yes, nature is full of mockery! Why"—he continued with sudden warmth—"does she create the choicest beings only to mock at them? The only human being who is recognized as perfect, when nature showed him to mankind, was given the mission to say things which have caused the shedding of so much blood that it would have drowned mankind if it had all been shed at once!"

This unsuccessful attempt at perfection causes Ippolit to hate Myshkin, whom he sees as an imitator of Christ. To Ippolit, Myshkin is purposely naive and only chooses to see the best in people. His hate is unchanging, unlike that of Rogozhin. Like the latter, Ippolit threatens to kill Myshkin, though he chooses not to do so because he himself is about to die. He "wanted to live for the happiness of all men, to discover and proclaim the truth," but his life is being cut short; he despises the prince for possibly being able to do what he has been denied.

He had an intelligent face, though it was usually irritated and fretful in expression. His skeleton-like figure, his ghastly complexion, the brightness of his eyes, and the red spots of colour on his cheeks, betrayed the victim of consumption to the most casual glance. He coughed persistently, and panted for breath; it looked as though he had but a few weeks more to live.

He appears in Part II with the band of accusers of Myshkin who seek to extort money from the prince. Though he apparently is unaware of the plot, he tries to help make the case that the prince should surrender his inheritance. When Ganya reveals the truth, Ippolit accepts it, though he is offended that Myshkin will still attempt to offer some money to his accusers.

Kolya describes him as clever but a "slave to his opinions." An atheist, Ippolit describes nature as ironical and accuses Christ of being leader of a genocidal movement:

"Yes, nature is full of mockery! Why"—he continued with sudden warmth—"does she create the choicest beings only to mock at them? The only human being who is recognized as perfect, when nature showed him to mankind, was given the mission to say things which have caused the shedding of so much blood that it would have drowned mankind if it had all been shed at once!"

This unsuccessful attempt at perfection causes Ippolit to hate Myshkin, whom he sees as an imitator of Christ. To Ippolit, Myshkin is purposely naive and only chooses to see the best in people. His hate is unchanging, unlike that of Rogozhin. Like the latter, Ippolit threatens to kill Myshkin, though he chooses not to do so because he himself is about to die. He "wanted to live for the happiness of all men, to discover and proclaim the truth," but his life is being cut short; he despises the prince for possibly being able to do what he has been denied.

Friday, March 12, 2010

The Woman Question

A girl grows up at home, and suddenly in the middle of the street she jumps into a cab: 'Mother, I was married the other day to some Karlitch or Ivanitch, goodbye.' And is it the right thing to behave like that, do you think? Is it natural, is it deserving of respect? The woman question? This silly boy--she pointed to Kolya--even he was arguing the other day that that's what 'the woman question' means....They regard society as savage and in human, because it cries shame on the seduced girl; but if you think society inhuman, you must think that the girl suffers from the censure of society, and if she does, how is it you expose her to society in the newspaper and expect her not to suffer? (Part II, Ch. 9)

After Myshkin becomes the victim of an extortion attempt, Madame Epanchin expresses displeasure with Myshkin for being gullible but also chastises those who tried to take the latter's mone. In the above passage, Dostoevsky divulges his conservative views and references Natasya without saying her name.

Madame Epanchin reproves those who seek to prey on Myshkin's generosity in order to claim money to which they have no legal right. They know he will grant them money they do not deserve because, as Myshkin reasons, they would not go through with such a scheme unless they really needed the money. Nevertheless, Madame Epanchin points out that just because Myshkin is willing to, and likely will, give them the money does not make them any less despicable. She brings up the "woman question" to make the point that the end does not justify the means.

The second part of the quote makes the point that it is hypocrital to proclaim society unjust and then participate in society's unjust treatment of an individual. Though the point made corresponds to the earlier part of her tirade, there is an implicit reference to Natasya, who has not appeared in Part II but has mostly been on the run from Rogozhin. However, the suggestion of her causes the reader to recall her importance to the narrative and may signal an imminent reappearance.

The above painting is Spring Maiden (1884) by Frank Dicksee.

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

The Poor Knight

After leaving Rogozhin's house, Myshkin, while waiting to meet Kolya at a nearby hotel, is attacked and nearly killed by Rogozhin, only saved by an epileptic fit. Myshkin is transported to Pavlovsk and is reunited with the cast of characters from Part I. The Epanchins visit him at Lebedyev's house and while there, Koyla brings up Pushkin's poem The Poor Knight and the visitors implicitly compare the poem's quixotic protagonist to Myshkin. Aglaia begins to sympathize with Myshkin and declares that she loves the idealistic knight and recites the poem for everyone.

The poem describes a "poor and simple" knight who has a vision of the virgin Mary and, as a result, gives up all fleshly desires and devotes himself fully to the cause of the Church by fighting against infidels. Afterwards he returns to his home and dies alone and "bereft of reason."

While the other characters laugh at the poor knight, Aglaia begins to defends him as "a man who having once set an ideal before him has faith in it, and having faith in it gives up his life blindly to it." His vision of "some image of pure beauty" caused him to become completely dedicated to her and "if she became a thief afterwards, he would still be bound to believe in her." Aglaia makes it very clear to whom she is referring during her recitation of the poem when she substitutes N.F.B. for the letter A.M.D. (Ave, Mater Dei). N.F.B. are Natasya's initials and the poor knight is Myshkin. Upon seeing a picture of Natasya, Myshkin took her outer beauty to be indicative of her inner beauty and becomes devoted to saving her from the terror of Rogozhin. Aglaia believes that Myshkin's cause is noble. Is Myshkin willing to die for his cause?

The above painting is The Faithful Knight (1900-1905) by Frederick Marriott.

The poem describes a "poor and simple" knight who has a vision of the virgin Mary and, as a result, gives up all fleshly desires and devotes himself fully to the cause of the Church by fighting against infidels. Afterwards he returns to his home and dies alone and "bereft of reason."

While the other characters laugh at the poor knight, Aglaia begins to defends him as "a man who having once set an ideal before him has faith in it, and having faith in it gives up his life blindly to it." His vision of "some image of pure beauty" caused him to become completely dedicated to her and "if she became a thief afterwards, he would still be bound to believe in her." Aglaia makes it very clear to whom she is referring during her recitation of the poem when she substitutes N.F.B. for the letter A.M.D. (Ave, Mater Dei). N.F.B. are Natasya's initials and the poor knight is Myshkin. Upon seeing a picture of Natasya, Myshkin took her outer beauty to be indicative of her inner beauty and becomes devoted to saving her from the terror of Rogozhin. Aglaia believes that Myshkin's cause is noble. Is Myshkin willing to die for his cause?

The above painting is The Faithful Knight (1900-1905) by Frederick Marriott.

Monday, March 8, 2010

Rogozhin

Before heading to Pavlovsk, Myshkin decides to place a visit to a residence on Gorohovy Street which is described as a "large gloomy house" of a "dirty green color" with "very few windows" of a "inhospitable and frigid" character, as if "keeping something dark and hidden." Though seeing the residence for the first time, Myshkin immediately recognizes it as the home of Rogozhin which he shares with his mother and brother. Everything on the inside of the house is dark, causing Myshkin to remark, "It's so dark! You are living here in darkness." The one exception is a painting by Hans Holbein, Dead Christ, which catches Myshkin's attention and provokes a discussion about Christianity.

The house is a perfect reflection of Rogozhin himself. Everything about him is dark and hidden; the reader still does not understand his character, though he has made several appearances. He has gone from helping Myshkin locate the Epanchins to a man obsessed with Natasya Filippovna. He loves her violently, one time beating her for cheating with Keller, afterwards not eating or sleeping for 36 hours. Myshkin tells him, "There's no distinguishing your love from hate," and says, "Any man would be better than you, because you really may murder her," repeating an idea he stated earlier in the novel to Ganya. Myshkin, with whom Rogozhin recognizes Natasya is in love, distinguishes his love by stating, "I don't love her with love, but with pity." Both men love her but Rogozhin's is an unhealthy love.

Natasya has run away from Rogozhin to Myshkin several times but always returns to Rogozhin, sensing she would ruin Myshkin. Therefore, Myshkin has become a sort of rival to Rogozhin. Myshkin has felt that Rogozhin has been following him several times, though Rogozhin denies it. Myshkin does not feel confortable around him and describes his "friendly smile" as "very unbecoming." Rogozhin admits that he likes Myshkin while they are together but starts to hate him when they do not see one another, which explains his attack on Myshkin shortly after the latter leaves the residence. The two exchange crosses, a sign that both are seeking salvation. Apparently, Myshkin is looked upon as a savior by both Rogozhin and Natasya, the former needing salvation from his violent passion and the latter needing salvation from her past. Myshkin tells Rogozhin, "You are passionate in everything; you push everything to a passion," a trait that can be traced to his father, who was a Skoptsy, a Christian sect of Russian self-mutilators.

The house is a perfect reflection of Rogozhin himself. Everything about him is dark and hidden; the reader still does not understand his character, though he has made several appearances. He has gone from helping Myshkin locate the Epanchins to a man obsessed with Natasya Filippovna. He loves her violently, one time beating her for cheating with Keller, afterwards not eating or sleeping for 36 hours. Myshkin tells him, "There's no distinguishing your love from hate," and says, "Any man would be better than you, because you really may murder her," repeating an idea he stated earlier in the novel to Ganya. Myshkin, with whom Rogozhin recognizes Natasya is in love, distinguishes his love by stating, "I don't love her with love, but with pity." Both men love her but Rogozhin's is an unhealthy love.

Natasya has run away from Rogozhin to Myshkin several times but always returns to Rogozhin, sensing she would ruin Myshkin. Therefore, Myshkin has become a sort of rival to Rogozhin. Myshkin has felt that Rogozhin has been following him several times, though Rogozhin denies it. Myshkin does not feel confortable around him and describes his "friendly smile" as "very unbecoming." Rogozhin admits that he likes Myshkin while they are together but starts to hate him when they do not see one another, which explains his attack on Myshkin shortly after the latter leaves the residence. The two exchange crosses, a sign that both are seeking salvation. Apparently, Myshkin is looked upon as a savior by both Rogozhin and Natasya, the former needing salvation from his violent passion and the latter needing salvation from her past. Myshkin tells Rogozhin, "You are passionate in everything; you push everything to a passion," a trait that can be traced to his father, who was a Skoptsy, a Christian sect of Russian self-mutilators.

Saturday, March 6, 2010

Pavlovsk

The book Literary Russia creates a literary map of that country that details the roles different areas of the country have played in Russian literature. This book can be an invaluable source to those unfamiliar with the vast nation. In relation to The Idiot, the book assists in keeping track of the movement of the characters. For example, one learns that the Epanchins live near Liteiny Prospect, a wealthy street in St. Petersberg where Ptitsyn wants to live eventually.

In Part II, the action of the novel shifts from St. Petersberg to Pavlovsk, located about 16 miles south of the former in the western part of Russia near the border with present-day Estonia. The city is famous for a palace Catherine the Great built there for her son Paul I in the latter part of the 18th century. It is known as a holiday town, and the Epanchins have a summer villa there and Lebedyev tells Myshkin he is heading there as well. Lebedyev explains, "It's nice and high up, and green and cheap and bon ton (fashionable) and musical--and that's why everyone goes to Pavlovsk."

In Part II, the action of the novel shifts from St. Petersberg to Pavlovsk, located about 16 miles south of the former in the western part of Russia near the border with present-day Estonia. The city is famous for a palace Catherine the Great built there for her son Paul I in the latter part of the 18th century. It is known as a holiday town, and the Epanchins have a summer villa there and Lebedyev tells Myshkin he is heading there as well. Lebedyev explains, "It's nice and high up, and green and cheap and bon ton (fashionable) and musical--and that's why everyone goes to Pavlovsk."The description of Pavlovsk contrasts with that of St. Petersberg six months earlier when Myshkin first arrives from Switzerland. The latter is described as "thawing, and so damp and foggy" while Pavlovsk is full of life and action. Pavlovsk is a change of scenery that allows the characters to get away from the chaos of St. Petersberg.

Pictures of autumnal Pavlovsk can be seen here.

Thursday, March 4, 2010

What is Love?

After reading Part I, one question that may come to mind is, are any of the characters mentioned so far capable of love?

- Myshkin-Yes, but only on a limited basis. The story of Marie as well as his interaction with Nastasya Filippovna show that he does not know how to love but can sympathize with others and can believe that others are genuinely good. He exhibits the purest form of love possible.

- Ganya-Is willing to marry someone her does not love and give the one he truly does love all for money. One wonders if he can truly love Aglaia if he will willing to allow his pride and love of money prevent him from being with her

- Rogozhin-Seems to view Natasya as a possession that he must have. Nastasya willingly runs off with him because she cannot ruin him, suggesting he is already corrupt.

- Totsky-The seducer of Natasya who wants to marry an Epanchin daughter. His treatment of Natasya and willingness to pay Ganya to be rid of him suggest he is not capable of true love.

- General Epanchin-Though married, he gives Natasya expensive pearls, suggesting he may have had his eye on her as well. Natasya later returns those pearls.

- General Ivolgin-Married as well, but has a mistress he visits and gives her money.

- Natasya-Does not love herself and cannot love anyone else. Events from her youth have caused her to view love pessimistically.

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

Character Analysis: Ganya

Gavril Ardalionovitch Ivolgin, called Ganya for short, is the secretary for the General Epanchin who befriends Myshkin and allows him to stay with his family upon arriving in St. Petersberg. He has schemed with the general and Totsky to marry Natasya, receiving an incentive of 75,000 roubles, though he really loves Aglaia. He writes her a note stating, "One word--one word only from you and I am saved"--saved, that is, from his marriage to Natasya. However, Aglaia responds, "I don't make bargains." At Natasya's party, Rogozhin shows up with 100,000 roubles and offers them to Natasya for her hand. She offers the money to Ganya but throws the bundle into the fireplace and tells Ganya he must retrieve it if he wants it. Ganya desperately wants the money but holds himself back to the point that he faints, and Natasya retrieves the bundle and lays it besides his unconscious body. Natasya declares that "his vanity is even greater than his love of money."

While Myshkin wants to sacrifice himself for Natasya because he truly believes in her, Ganya wants to sacrifice himself for Natasya because of the money that marriage promises. He is actually in love Aglaia and wants the latter to make the decision for him so he can blame her if he has regrets, but she refuses to be used in this way. Myshkin calls him "weak and unoriginal," and Ganya responds that "when I have money, I shall become a highly original man." Of course, Ganya fails to realize that originality can be a way of obtaining money. Instead, embarassed by his family's poverty, Ganya decides to pursue the easiest way of obtaining money: getting paid to marry someone he does not love and who does not love him. When he faints from the strain of trying to decide whether to retrieve the bundle from the fire, Natasya recognizes that his pride prevents him from making a move, though he desires the money. Apparently, he is willing to sacrifice anything to obtain money, except his own pride.

The above painting is The Hireling Shepherd (1851) by William Holman Hunt.

The above painting is The Hireling Shepherd (1851) by William Holman Hunt.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

The Party

Myshkin shows up unexpectedly at Natasya's birthday party where she decides to announce her marriage plans. Totsky (her seducer and benefactor), General Epanchin, Ganya, and Rogozhin are among the guests that have a strong interest in her decision. Natasya shows surprise as well as pleasure at his appearance, and proceeds to asks Myshkin if she should marry Ganya. Sensing that Ganya does not truly lover her, Myshkin responds that she should not, throwing the company into an uproar. After lamenting that no one but Rogozhin could love her because she has nothing, Natasya is shocked at Myshkin's declaration of love and his calling her an "honest woman." Though flattered, Natasya states that she doesn't want to ruin Myshkin and runs away with Rogozhin. Thus Part I of The Idiot ends.

Myshkin shows up unexpectedly at Natasya's birthday party where she decides to announce her marriage plans. Totsky (her seducer and benefactor), General Epanchin, Ganya, and Rogozhin are among the guests that have a strong interest in her decision. Natasya shows surprise as well as pleasure at his appearance, and proceeds to asks Myshkin if she should marry Ganya. Sensing that Ganya does not truly lover her, Myshkin responds that she should not, throwing the company into an uproar. After lamenting that no one but Rogozhin could love her because she has nothing, Natasya is shocked at Myshkin's declaration of love and his calling her an "honest woman." Though flattered, Natasya states that she doesn't want to ruin Myshkin and runs away with Rogozhin. Thus Part I of The Idiot ends.Natasya has never had a man truly love her: Totsky seduced her as a young girl and was done with her, Ganya just wants the money that marriage to her promises, and Rogozhin loves her beauty but wants to control her. Though she takes her bad reputation to heart, Myshkin sees her as a good woman in whom "everything is perfection." When Natasya rejects his proposal, it is because she feels obligated to live up to her reputation. She is willing to sacrifice herself to a relationship because she has little self-worth, but Myshkin is the first to claim that she is more than worthy of his love. She cannot be with Myshkin because he values her more than she values herself, which is foreign territory to Natasya.

The above painting is, The Awakening Conscience (1853) by William Holman Hunt