A blog detailing particularly novels, but also poems, plays, and social essays from the Victorian era, though strict adherence to the period of Queen Victoria's reign (1837-1901) may not be observed. Blog will also feature some American, French, and Russian works of the period.

Sunday, February 28, 2010

Natasya Filippovna

Upon leaving the Epanchin household, Myshkin goes with Ganya, the secretary of General Epanchin, to the home of Ganya's parents. Ganya is ashamed of his family in general because of their poverty and of his father, General Ivolgin, in particular because of his tendency to make up stories. General Ivolgin tells Myshkin that he knew his father, which isn't true, though Prince listens to his story politely.

At this point, a new character is introduced who has been referred to many times by several different characters. Natasya shows up unannounced at the Ivolgin home, much to the embarrassment of Ganya, who, though truly in love with Aglaia, an Epanchin daughter, has been offered a significant sum to marry Natasya. General Ivolgin introduces himself to Natasya and proceeds to tell her how he once threw a dog out of a train window after that dog's own performed the same action to a cigar he was smoking. General Ivolgin becomes flustered when Natasya points out she had read the same story from a newspaper a week prior.

Natasya is a woman who has been mistreated by men. She was adopted by Totsky, a rich man who once seduced her but who now at 55 is ready to be rid of Natasya so he can marry one of the Epanchin daughters, Alexandra. He has promised Natasya 75,000 roubles and Natasya realizes that Ganya is only agreeing to the marriage due to pecuniary interests. At the same time she is involved with Rogozhin, who is in love with her but who Myshkin declares would marry Natasya and murder her a week later.

It is at this moment that Natasya meets Prince, who is enraptured with her beauty. Myshkin shows strong emotion but is quiet in her presence. Natasya herself seems intrigued by Prince but is too distracted by everything going on around her to pay him much attention. However, Dostoevsky suggests that this is only the beginning of an interesting relatioship between the two.

Friday, February 26, 2010

Marie

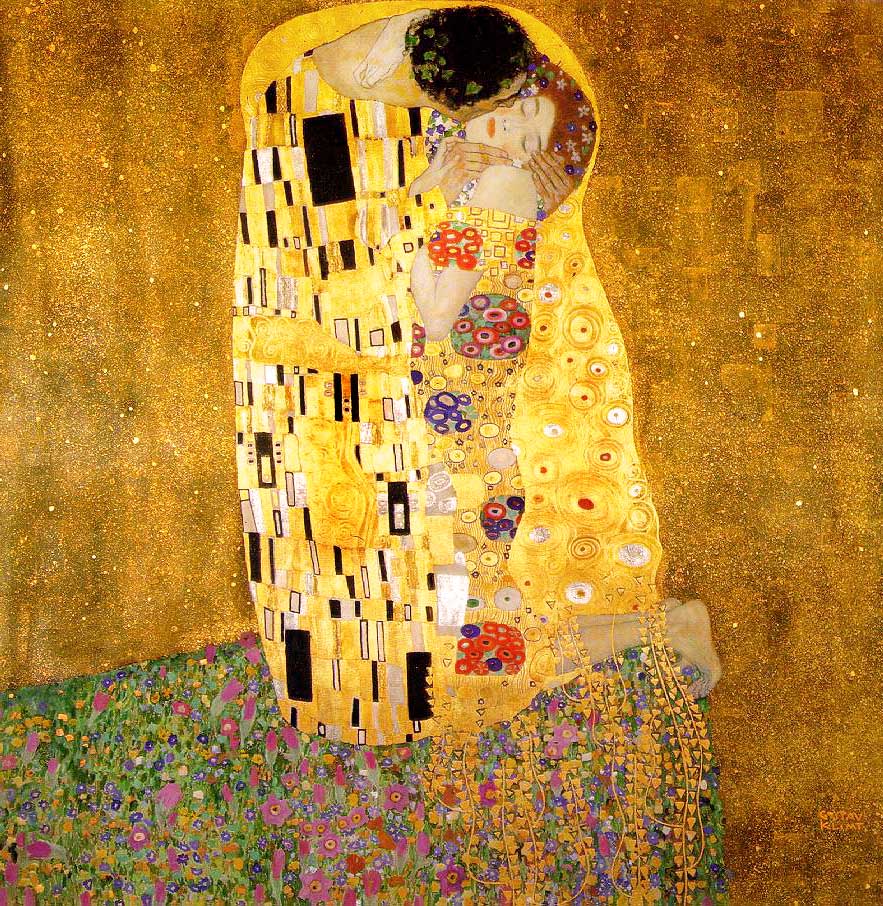

After introducing himself to the Epanchin family, Prince Myshkin shares his views, though the family laughs at him periodically. Though he states that he has never been in love, Myshkin tells the family about a girl named Marie whom he met in Switzerland. She was a young girl, weak and thin from consumption, who was seduced and taken away by a French traveller, who abandoned her a week later. Upon her return home, she was rejected by everyone, including her mother, and viewed in her own eyes as the lowest of the low. Neverthless, the children that lived near her embraced her after mother's death and were made to love her when they saw Myshkin kiss her one day. Myshkin declares that he kissed her only because he felt sorry for her. Marie eventually grows too weak to do any work and later dies. The children placed flowers on her grave to show their love for her.

One critic1 has stated that Myshkin "attempts to restore Marie to her unfallen condition rather than to love her in her sinfulness." The word "sinfulness" may be too strong (unpurity may be better). Myshkin thus far has not shown himself capable of being in love though he shows great compassion. Nevertheless, not only does he convince the children that Marie is worthy of their love, but he tries to convince her personally, particularly with a kiss. He does not offer a kiss of love but a kiss that signifies that she is palpable and not cursed. The love he offers is closer to brotherly love with no strings attached. Myshkin does love her in her "sinfulness" and others agree with him that she deserves their love.

An interesting passage details the children's reaction at the funeral:

There were not many people at the funeral, only a few, attracted by curiosity; but when the coffin had to be carried out, the children all rushed forawrd to carry it themselves. Though they were not strong enough to bear the weight of it alone, they helped carry it, and all ran after the coffin, crying. (Part I, Chapter 6)

The children cannot bear the weight of the casket alone but could help others to carry it. The weight of death is too much for them; they must rely on others to help them.

Myshkin states that the doctor that he lived with in Switzerland told him

I was a complete child myself, altogether a child; that it was only in face and figure that I was like a grown-up person, but that in development, in soul, in character, and perhaps in intelligence, I was not grown up, and that so I should remain, if I lived to be sixty.

Myshkin doesn't see himself as childlike; he calls the children they, not we. However, Myshkin is only capable of a childlike love. He is able to empathize with other and show sympathy but is not capable of falling in love. The story of Marie foreshadows his interaction with Natasya.

1--D.P Slattery, The Idiot: Dostoevsky's Prince, 1983, p. 56

The above painting is The Kiss (1908) by Gustav Klimt

Tuesday, February 23, 2010

To St. Petersberg

The novel opens on a train ride in which Prince Myshkin, the title character, Rogozhin, and Lebedyev all head to St. Petersberg. Myshkin is traveling from Switzerland and is trying to located a distant relative who has since married into the Epanchin family. Myshkin shows up at the Epanchin home apparently inappropriately dressed as a guest in this residence and gets into a discussion with a servant about Russia's new judicial system and capital punishment.

Prince recalls witnessing a man being guillotined in France. In talking about the man's final moments, Dostoevsky is recalling his own death sentence that was later commuted. He describes how grief-stricken the man is crying uncontrollably and how his final moments are worse than torture because one knows the hour one will die and there is no hope. In other instances of possible death, there is always hope but when one is given a sentence of death, the final hours are more agonizing than anything imaginable.

To kill for murder is a punishment incomparably worse than the crime itself. Murder by legal sentence is immeasurably more terrible than murder by brigands. Anyone murdered by brigands, whose throat is cut at night in a wood, or something of that sort, must surely hope to escape till the very last minute. There have been instances when a man has still hoped for escape, running or begging for mercy after his throat was cut. But in the other case all that last hope, which makes dying ten times as easy, is taken away for certain. There is the sentence, and the whole awful torture lies in the fact that there is certainly no escape, and there is no torture in the world more terrible. (Part I , chapter 2)

As will be evident later, Myshkin places a strong emphasis on the element of hope. He has a unique ability to empathize with others and show pity. Myshkin acknowledges that there may be a man sentenced to death that is later told that he may go (as was Dostoevsky), but the convict is submitted to another that must make that decision and can in no way influence that decision. For this reason, Myshkin praises Russia for having no capital punishment. Dostoevsky will continue to return to this issue of a man suffering.

Prince recalls witnessing a man being guillotined in France. In talking about the man's final moments, Dostoevsky is recalling his own death sentence that was later commuted. He describes how grief-stricken the man is crying uncontrollably and how his final moments are worse than torture because one knows the hour one will die and there is no hope. In other instances of possible death, there is always hope but when one is given a sentence of death, the final hours are more agonizing than anything imaginable.

To kill for murder is a punishment incomparably worse than the crime itself. Murder by legal sentence is immeasurably more terrible than murder by brigands. Anyone murdered by brigands, whose throat is cut at night in a wood, or something of that sort, must surely hope to escape till the very last minute. There have been instances when a man has still hoped for escape, running or begging for mercy after his throat was cut. But in the other case all that last hope, which makes dying ten times as easy, is taken away for certain. There is the sentence, and the whole awful torture lies in the fact that there is certainly no escape, and there is no torture in the world more terrible. (Part I , chapter 2)

As will be evident later, Myshkin places a strong emphasis on the element of hope. He has a unique ability to empathize with others and show pity. Myshkin acknowledges that there may be a man sentenced to death that is later told that he may go (as was Dostoevsky), but the convict is submitted to another that must make that decision and can in no way influence that decision. For this reason, Myshkin praises Russia for having no capital punishment. Dostoevsky will continue to return to this issue of a man suffering.

Saturday, February 20, 2010

Russia in the 1860s

Upon the death of Tsar Nicholas I, Alexander I (1855-1881) inherited the Russian throne and instituted a series of reforms in an effort to modernize Russia. One of his most significant reforms was the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. Thinking that it would be better for change to come above than from below, Alexander II began a 3 year process that liberated 50 million serfs during the same time as the US Civil War.

Among his other reforms was instituting elected local assemblies, though not national assembly followed. He also modernized Russia's judicial system, which resulted in a clearer codification of the laws and better qualified judges. He also reformed the education system, one result being opening up elementary education to all classes. Finally, the network of railways was extended nearly 20 times its size in 1857. Not only did this connect remote parts of Russia but it also stimulated trade, particularly the grain trade.

In the midst of these sweeping reforms, Dostoevsky wrote The Idiot. In the novel, Dostoevsky gives his view of the quickly changing Russia in which he lived.

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky (1821-1881) was the son of a former army surgeon, who was murdered by his own serfs for his brutality. He received a military education but never pursued such a career and turned to writing instead, publishing his first novel Poor Folk in 1846. His writing career was halted in 1849, following his arrest for alleged subversion against Tsar Nicholas I.

After a lenghty sentence, which included four years of forced labor in Siberia, Dostoevsky went on to write four major novels between 1866 and and 1880 (Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, The Possessed, and The Brothers Karamazov). Part of the motivation behind his prolific output was his huge gambling debts.

The Idiot was Dostoevsky second major novel. In it, he sought to portray a saintly man devoid of ulterior motives in his desire to help people. His protagonist is an epileptic, a condition Dostoevsky himself developed during his time in Siberia. Also, during the writing of the novel, Dostoevsky was devastated by the loss of his infant daughter Sonya.

Monday, February 15, 2010

The Conclusion

"Ah! Vanitas Vanitatum! which of us is happy in this world? Which of us has his desire? or, having it, is satisfied?—come, children, let us shut up the box and the puppets, for our play is played out."

The above quote are the final lines from Vanity Fair. Thackeray goes back to his idea in the preface that no one is truly happy in Vanity Fair. As for those in the novel:

*Becky seems to be happy, as a result of her financial security due to Jos' insurance policy and her stipend from her son Rawdon. Thackeray details how she regularly attends church and gives to charity. However, her pursuits have cost her her husband, her son, and a friend in Amelia. Nevertheless, Thackeray causes us to consider that Becky was right when she states, "I think I could be a good woman if I had five thousand a year."

*Amelia has finally gotten past the death of George and is able to embrace Dobbin as a husband. They have a daughter named Jane, and Amelia is convinced that Dobbin is more affectionate toward Jane than herself.

*Dobbin himself finally has the wife he has wanted for 18 years. Whether she is worthy of his love, he had already questioned earlier in the novel but he does love her and his daughter.

Thus our venture into Vanity Fair has ended.

The above quote are the final lines from Vanity Fair. Thackeray goes back to his idea in the preface that no one is truly happy in Vanity Fair. As for those in the novel:

*Becky seems to be happy, as a result of her financial security due to Jos' insurance policy and her stipend from her son Rawdon. Thackeray details how she regularly attends church and gives to charity. However, her pursuits have cost her her husband, her son, and a friend in Amelia. Nevertheless, Thackeray causes us to consider that Becky was right when she states, "I think I could be a good woman if I had five thousand a year."

*Amelia has finally gotten past the death of George and is able to embrace Dobbin as a husband. They have a daughter named Jane, and Amelia is convinced that Dobbin is more affectionate toward Jane than herself.

*Dobbin himself finally has the wife he has wanted for 18 years. Whether she is worthy of his love, he had already questioned earlier in the novel but he does love her and his daughter.

Thus our venture into Vanity Fair has ended.

Saturday, February 13, 2010

The Charades of Becky (cont'd)

Thackeray's second allusion used to describe Becky's character is to Clytemnestra, the wife of King Agamemnon, who became her husband upon killing her first husband. When Agamemnon sacrifices their daughter Iphigenia, an embittered Clytemnestra along with her new lover Aegisthus plot the murder of the king. Upon Agamemnon's return from the Trojan War, Clytemnestra get revenge by stabbing and killing her husband.

At a party at Lord Steyne's house, a game of charades was started up (a popular form of entertainment at the time) and in the final scene, Rawdon appears as Agamemnon and Clytemnestra makes her appearance as well:

Clytemnestra glides swiftly into the room like an apparition--her arms bare and white,--her tawny hair floats down her shoulders,--her face is deadly pale,--and her eyes lighted up with a smile so ghastly, that people quake as they look at her'

A tremor ran through the room. "Good God!" somebody said, "it's Mrs. Rawdon Crawley."

The darkness and the scene frightened people. Rebecca performed the part so well, and with such ghastly truth, that the spectators were all dumb, until, with a burst, all the lamps of the hall blazed out again, when everybody began to shout applause. (Chapter 51)

Becky is so convincing in her performance that even Steyne says to himself, "By --, she'd do it too." Thackeray includes the episode mostly to describe Becky's character rather than to draw parallels.

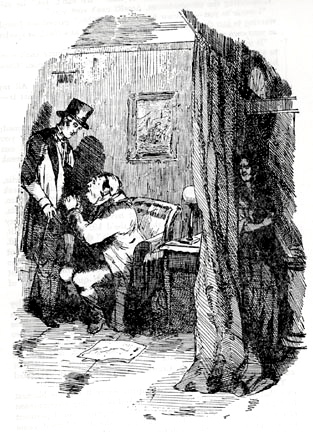

Thackeray reinforces the idea of Becky as a Clytemnestra in the penultimate illustration of the novel entitled, "Becky's second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra." The illustration depicts Becky behind a curtain listening to Dobbin and Jos Sedley, with whom Becky reconnected after being abandoned by everyone, having a conversation about Jos's fears that Becky would kill him if he left her too. Becky is armed with either a dagger or a vial of poison, but the actual text gives no indication that Becky is in the room. Jos dies three months later and Becky collects his insurance money, causing many to suspect that Becky played a role in his death.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

The Charades of Becky

Thackeray uses two allusions to help the reader understand Becky's character. One of these characterizations is as Delilah, the biblical temptress that ensnared Samson and secured his capture by the Philistines. Thackeray first uses this allusion after the marriage of Becky and Rawdon is revealed:

"how she sings,--how she paints!" thought he. "How she rode that kicking mare at Queen's Crawley!" And he would say to her in confidential moments, "By Jove, Beck, you're fit to be Commander-in-Chief, or Archbishop of Canterbury, by Jove." Is his case a rare one? and don't we see every day in the world many honest Hercules at the apronstrings of Omphale*, and great whiskered Samsons prostrate in Delilah's lap? (Chapter 16)

Delilah, like Becky, was deceptive and cunning and uses Samson for monetary gain. Becky later acknowledges the pecuniary motive when she says, "I'll make your fortune," she said; and Delilah patted Samson's cheek. (Chapter 16)

Moreover, Delilah knew how to manipulate and get what she wanted.

He (Rawdon) was beat and cowed into laziness and submission, and Delilah had imprisoned him and cut his hair off too. The bold and reckless young blood of ten years back was subjugated, and was turned into a torpid, submission, middle-aged, stout gentleman.

Becky basically stripped Rawdon of his masculinity and takes his strength (in Samson's case, his hair) from him. He has become totally dependent on Becky for income, which she obtains from Lord Steyne. However, Delilah also provides the element of being ensnared; does Thackeray mean to suggest that Becky ensnares Rawdon? One must remember that Rawdon (like Samson) realy does love Becky, though Becky's feelings for Rawdon are not so evident. Becky seems incapable of love, as she does not even love her own son.

*Hercules was made subservient to Omphale for a year for his murder of Iphitus.

The painting above is Samson and Delilah (1625) by Gerrit van Honhorst.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

The Steyne Affair

Another Jewish character Becky encounters is Lord Steyne, a very rich member of the English aristocracy. He allegedly won his wife at a gaming table, and upon meeting Becky, encourages her to neglect little Rawdon. He lives in the appropriately named Gaunt House, a dilapidated edifice located in a neighborhood with "a dreary look" of "tall, dark houses" inhabited by "a few miserable governesses with wan-faced pupils."

Steyne's attention to Becky seems to be a secret to no one but Rawdon. Becky uses Steyne to obtain money and jewelry, though Rawdon has no idea where any of it is coming from. Upon finding Bey and Steyne alone, Rawdon realizes that Becky has been receiving gifs from Steyne and challenges the latter to a duel. He eventually backs down from the challenge and abandons Becky for good by taking the governorship of Coventry Island, a position obtained for him by Steyne. Steyne completely dismisses Becky and never talks to her again.

Steyne's attention to Becky seems to be a secret to no one but Rawdon. Becky uses Steyne to obtain money and jewelry, though Rawdon has no idea where any of it is coming from. Upon finding Bey and Steyne alone, Rawdon realizes that Becky has been receiving gifs from Steyne and challenges the latter to a duel. He eventually backs down from the challenge and abandons Becky for good by taking the governorship of Coventry Island, a position obtained for him by Steyne. Steyne completely dismisses Becky and never talks to her again.

Saturday, February 6, 2010

Will Dobbin

Will Dobbin is one of maybe two characters in the novel who is inherently good (the other being Amelia). He is a childhood friend of George Osborne and once defends George from the school bully. It is a selfless act of someone who endures being made fun of as the son of a grocer. Dobbin is often looking out for the interests of others and rarely pursues his own interests. The only true interest Dobbin displays is his interest in Amelia, which he doesn't pursue because she is in love with the unworthy George.

Dobbin often acts behind the scenes in order to avoid recognition for the good he performs. In one instance, he purchases Amelia's piano at her family's auction and sends it to her annonymously. Unfortunately for Dobbin, Amelia assumes it's from George and doesn't find out otherwise until the end of the novel. Dobbin hides his true feelings for Amelia, even after the death of George.

In another instance, Dobbin works behind the scenes to soften the Osbornes toward Amelia so that they may help Amelia's son Georgy move up in the world. He tells Georgy about his father, India, and Waterloo and mentors the young man.

In the above passage, Dobbin has more of a fatherly influence on George than anyone has before and discourages his arrogance, unlike his father's family. Dobbin becomes George's hero. much like he was for the late George Osborne.

Dobbin often acts behind the scenes in order to avoid recognition for the good he performs. In one instance, he purchases Amelia's piano at her family's auction and sends it to her annonymously. Unfortunately for Dobbin, Amelia assumes it's from George and doesn't find out otherwise until the end of the novel. Dobbin hides his true feelings for Amelia, even after the death of George.

In another instance, Dobbin works behind the scenes to soften the Osbornes toward Amelia so that they may help Amelia's son Georgy move up in the world. He tells Georgy about his father, India, and Waterloo and mentors the young man.

"One day, taking him to the play, and the boy declining to go into the pit because it was vulgar, the Major took him to the boxes, left him there, and went down himself to the pit. He had not been seated there very long, before he felt an arm thrust under his, and a dandy little hand in a kid-glove squeezing his arm. George had seen the obsurdity of his ways, and come down from the upper region. A tender laugh o benevolence lighted up old Dobbin's face and eyes as he looked at the repentant little prodigal. He loved the boy, as he did everything that belonged to Amelia. How charmed she was when she heard of this instance of George's goodness! Her eyes looked more kindly on Dobbin than they ever had done." (Chapter 60)

Wednesday, February 3, 2010

Miss Crawley

Matilda Crawley is the aunt of Rawdon, and prefers him over his brother Pitt, deciding to make Rawdon her heir of 70,000 pounds. She first meets Becky while the latter is governess for the Crawley daughters and decides to take Becky to stay with her. She states she loves imprudent matches and is intrigue by a possible match between Becky and her brother Sir Pitt Crawley (Rawdon's father), who approaches Becky about a match only a few days after his wife's death. However, she rejects the marriage of Rawdon and Becky, especially since she is convinced it is a scheme by Becky to get her money.

Miss Crawley is a viable resident in Vanity Fair. She indulges the flattery of her relatives who are seeking to get a part of her fortune. Her sister Mrs. Bute Crawley tries to get in her good graces after the departure of Becky but Matilda tires of her. Her nephew James tries a similar scheme and is politely asked to leave when the smoke from his pipe bothers his aunt. Sir Pitt's daughters are subservient to her every time she visits. She eventually replaces Rawdon with his brother Pitt as her heir, though neither likes the other.

Miss Crawley is a viable resident in Vanity Fair. She indulges the flattery of her relatives who are seeking to get a part of her fortune. Her sister Mrs. Bute Crawley tries to get in her good graces after the departure of Becky but Matilda tires of her. Her nephew James tries a similar scheme and is politely asked to leave when the smoke from his pipe bothers his aunt. Sir Pitt's daughters are subservient to her every time she visits. She eventually replaces Rawdon with his brother Pitt as her heir, though neither likes the other.